-Coachbuilding-

Brian Laak is an expert in wood, metal, and moving parts. So it was no surprise when Laak Woodworks entered the challenging and elite world of coachbuilding.

"Love of beauty is taste. The creation of beauty is art."

- Ralph Waldo Emerson

What is Coachbuilding?

The first cars were built by hand through a complex and multi-phase process. Coachbulding refers to the wooden skeleton of these early cars.

Cabinet builders were the first coachbuilders and we must retrace their steps when we restore one of these historic cars. The carpenter who attempts to renovate these stunning works of art must be able to produce precision complex curves. They must also have a detailed understanding of how every system will eventually come together to create the final product.

Part of Brian Laak's success with coachbuilding is due to his previous experience as mechanic. Brian has worked on WWII era Douglas DC3 airplanes, Volks Wagons, Audis, and Porsches. He also he has a passion for restoring classic English motorbikes. For his full biography click here. Together, these experiences make Brian uniquely qualified for the exclusive art of coachbuilding.

Currently, Laak Woodwork's has been commissioned to restore the wooden skeleton of Jacques Saoutchik's 1948 Talbot Lago T26 100114.

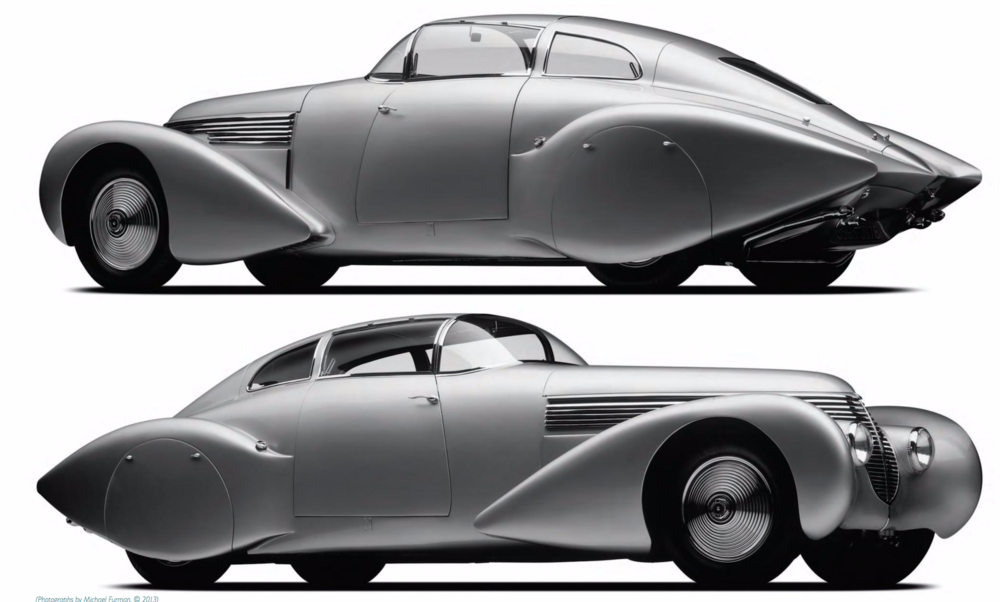

The Talbot Lago T26 Grand Sport 110114 in mint condition.

About Saoutchik's 1948 Talbot Lago T26 100114

Jacques Saoutchik was a master coachbuilder of the early 20th century known for his trendsetting extravagant designs. Like Brian Laak, he began his career as a cabinet maker. However, in 1906 Saoutchik transitioned and opened his own coachbuilding company, Carrosserie. His designs quickly gained a formidable reputation and he soon counted royalty among his clientele.

In 1948, Saoutchik debuted his Talbot Lago T26 110114 at the Concour d’Elegance exhibition. Since then, this iconic example of Saoutchik's later work has had several different owners from around the world. At times the car has been left idle for long periods and in harsh weather elements. These conditions lead to substantial rusting and wood rot.

In addition to this deterioration, the T26 110114 has received a series of major modifications and restorations over its lifetime. These changes include a removed and later reattached roof, the repair or replacement of most of its original parts, and the maintenance of the wooden skeleton by multiple skilled yet differently styled craftsman.

The current disassembled frame of the T26.

“The only way to restore a coach built car body properly is to carefully disassemble it, in order to restore it in the same sequence in which it was first built.”

- David Cooper

The Talbot Lago's Progress Gallery

To understand the complexity of this restoration,one must first understand the history of how these unique automotive machines were made.

Saoutchik creating a life-size body sketch

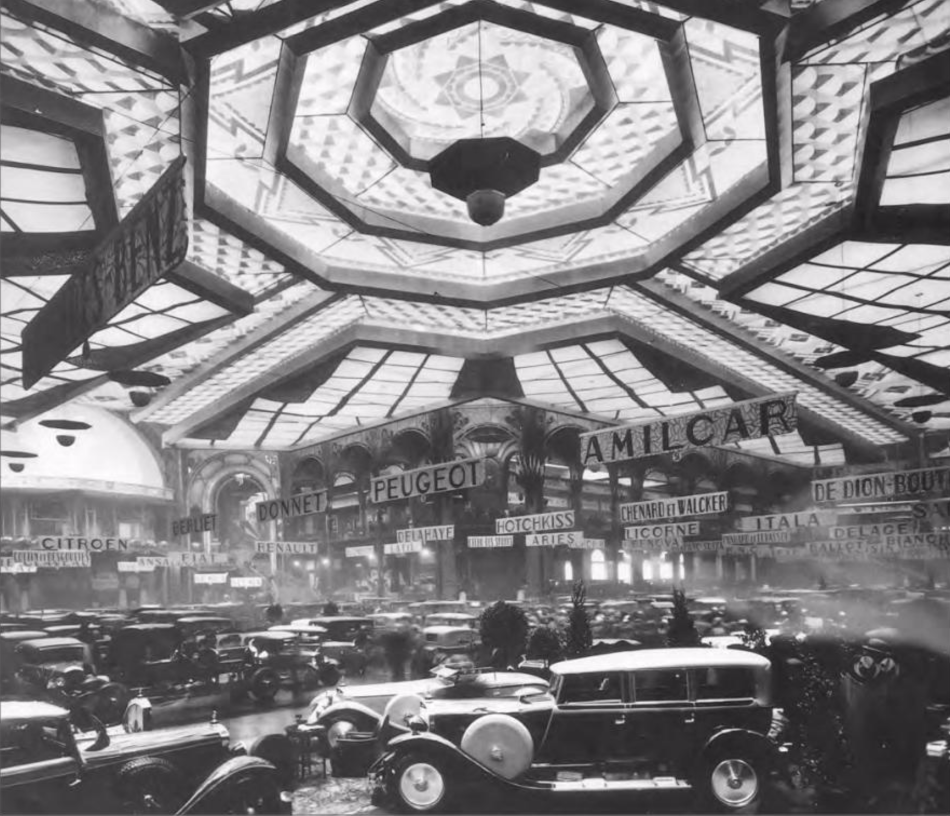

The History of the Coachbuilder

For the first half of the 20th century, automotive manufactures only made the chassis and power train. The chassis were delivered to a Coachbuilder who would design and build everything visible on the finished automobile; including the body, cabin, interior, doors, and fenders.

For luxury limited production vehicles, like the Talbot Lago T26 110114, a coachbuilder would work directly with the clients. Once the initial sketches and color rendering were approved, the coachbuilder would create life-sized drawings of the top and side views of the body. These sketches assisted in the process of building a life-sized body form called a maquette.

Maquettes would often be built out of wire frames and were used to give the coachbuilder and sheet metal craftsman a better visual aid when building the metal body. They then built maquettes from wooden bucks. These bucks were used for hammering and sculpting of the pre-shaped sheet metal into the finished body.

Wooden Skeletons

The Coachbuilder would build an internal wooden skeleton over the chassis. This skeleton was then wrapped with the metal panels and invisible in the finished car.

The wooden skeleton intentionally absorbed, transferred and dispersed vibrations, movement and energy throughout the vehicle. It also allowed cars to withstand extreme forces of wind, weather and flexing that occurred with higher speeds or uneven roads.

Ash was the traditional wood of choice for carriages and coaches for a few reasons:

· It has one of the best strength to weight ratios

· It is hard yet resilient

· It is less prone to water & insect damage

· It doesn’t break along grain lines

Wooden skeletons faded quickly in the 1950’s when they were replaced by a uni-body design for the mass production of cars.

THE CHALLENGES OF RESTORING THE T26 SKELETON

Laak Woodworks faces multiple challenges as we rebuild the wooden skeleton of the Talbot Lago T26 110114.

Challenge #1: Coachbuilding was a Proprietary Trade

Vintage coachbuilding is a dying art and before that it was a secret art.

Although never officially stated, coachbuilders remained incredibly secretive with many of their plans and manufacturing techniques. There are almost no photos of the coachbuilder’s workshops or their coaches as they were originally being built. Even with the dawn of the internet, there are very few resources detailing the exact processes used to build or restore coaches from this era. That leaves the majority of decisions on the T26 to be solved with our personal ingenuity, creativity and trade skills.

Challenge #2: Fitting to the Existing Metal Body

The broadest challenge of this restoration is rebuilding a wooden skeleton that is going to flawlessly fit into the salvaged sheet metal body. The T26 wooden skeleton and bucks were created side by side with the sheet metal body which allowed, to some degree, the metal to be shaped by the design of the wood.

In this case, Laak Woodworks needs to create a skeleton that is strongly determined by the pre-existing shapes of the metal body panels. It is crucial to both the form and function of the vehicle that we create a skeleton that closely partners the metal panels. David Cooper, who was responsible for documenting the restoration of similar Talbo Lago, mentions that his team realized that the skeleton needed to fit into the metal panels with only 2mm of forgiveness.

Challenge #3: Working with Previous Restorations

When examining the wooden frames of the doors, we can see that former restorers of the T26 worked diligently to save some of the original wood structure by sawing off rotted portions, joining new wood to the sawed off joints with glue or metal nails, and embedding the restored parts with resin to protect against further deterioration. Though these modifications seemed skillfully crafted, David Cooper makes another point that we have come to agree on:

“While the goal of saving the original [parts] whenever is admirable, a new wood part built from one portion old and one portion new, spliced and resin impregnated is in no way the same as the original part. Furthermore, the integrity of the vehicle and the function of the wood skeleton are compromised.”

With this knowledge in mind, we will only be using what remains of the original skeleton and metal body as references to build new wooden pieces from scratch.

Challenge #4: Replicating the Curves by Hand

Other restoration teams have been able to use laser scans and 3D modeling to produce highly accurate digital blueprints of an entire car and all of its major components. They can then build a wooden skeleton based off of the scans. From research, we have to presume that the cars being restored with this technology had metal body frames that held their true form which allowed them to create accurate digital maps. If this had been the best option available for the T26, we certainly would have done so.

Unfortunately, our T26 metal body no longer held her original curves. It also had thick layers of resin that have bonded with the metal leaving the surfaces uneven. This means laser scanning and 3D models are not an option. The shaping of the metal will only happen after the production of the new skeleton. Our estimates for curves must be handmade. Through the use of contour gauge duplicators, high-precision estimates and thorough research in the sparse amounts of original production information available, Laak Woodworks will recreate the skeleton and doors by hand.

The History of Jacques Saoutchik

Jacques Saoutchik was born in the Urkraine in 1880 and migrated to Paris in his early 20’s. As mentioned above, he began his career as cabinet maker but quickly transitioned into coachbuilding, opening his company Carrosserie in 1906. His first body was built on the chassis of a Isotta-Fraschini.

Saoutchik swiftly created a niche catering to top class automotive clients. His work became known for superior craftsmanship and originality and to this day, he is known as one of the most extravagant, eccentric and pioneering coachbuilders in automotive history. His incorporated elegant yet bold curvature and ornamental design into every aspect of his bodies.

Saoutchik line of custom cars became the iconic representation of Parisian chic in his era and his cars were decorated with awards at the infamous Concours d’Elegance, Paris Salon and other high society auto shows in Paris. His clients became more and more elite including the president of the Republic of Argentina, the King of Norway, celebrities, royal families, and even a pope-mobile for the pope himself.

In 1952, Saoutchik handed ownership of Carrosserie over to his son, Pierre Saoutchik. Saoutchik’s company closed its doors in 1955 as the world’s auto industry took a rapid restructuring that led to streamline Fordist automotive manufacturing, leaving little room for the custom manufacturing of cars like Saoutchik’s.

Most of the historical information and pictures on this page were sourced from the works of Peter M. Larsen, an automotive historian specializing in classic coachwork. Peter M. Larsen & Ben Erickson are the co-authors of the “The Kellner Affair” & “Talbot-Lago Grand Sport: The Car from Paris and Jacques Saoutchik: Maître Carrossier”. While the Talbot-Lago and Saoutchik books are out of print, The Kellner affair can be purchased from the publisher, Dalton-Watson Fine Books by clicking here.